JAMES DOUGLAS – Interview

James Douglas was born in Oshawa, Ontario Canada, and currently resides in Barkerville, British Columbia. He’s also spent time in the United States, studying acting in New York City. He studied Theatre History at the University of Victoria, as well as English Literature. When James switched from acting to screenwriting, his love for film and Stephen King collided, and in 2017 he brought Stephen King’s short story, THE DOCTOR’S CASE, to life.

When he isn’t filming, he’s busy writing, working as a manager for the Visitor Experience and Public Relations, in Barkersville Historic Town & Park. However, with the support from his wife, Danette Bee, and his own passion, James is becoming an unstoppable talent.

TN: You are originally from British Columbia, Canada, what was it like growing up there, and at what age did you first become a Stephen King fan? What was the first King book you read?

JD: Growing up in BC was magical, really. I was born in Oshawa, Ontario but moved across the country to the Okanagan Valley with my mom at a young age, so I definitely consider myself to be from British Columbia (and I couldn’t be happier about that). Living in Vernon, BC for the bulk of my early years meant equal parts outdoor recreation, indoor pursuits like music and theatre, and a healthy dose of striving to leave what I considered to be small town drudgery for the bright lights of a big city somewhere. Its funny, because when I go back to Vernon as an adult, I am reminded of what a progressive, exciting, and growing city it really is. Back then it seemed horribly small and boring. Now I very happily live in a secluded mountain town of 250 people. Go figure.

As for my Stephen King fandom: it began in earnest for me in the eighth grade. I had seen The Shining when I was ten or eleven years old some friends and I stayed up late one night at a sleepover to watch it on TV and I remember it scaring the hell out of me, but I hadn’t’ read any of Kings writing until I was thirteen. I can very clearly recall the circumstances, too.

In grade eight I was forced to take an Industrial Arts course because at the time they frowned upon boys taking Home Economics (which, to be honest, would have been much more useful to a latch-key kid like me). One of the four units of the course was on electricity, and I just couldn’t get into it. As a result, I never had my homework finished in time for class, as was required. Our teacher had a strict no homework policy: if you showed up to class and the work wasn’t done, you sat out in the hall for the remainder of the hour. I sat in the hall a lot, so a good friend of mine lent me a copy of Stephen Kings IT to help pass the time. I had hardly even seen a novel that big before, let alone read one that size, but I had nothing better to do. The second I started reading IT I knew I was in for the long haul. Three times a week during that class I sat in the hall devouring that book, and it fueled my subsequent passion for both Stephen King and literature in general. I wound up with an English Lit degree many years later, and I attribute that to my early exposure to reading (thanks, Mom and Dad), and specifically to those freshman afternoons reading IT in the hallway of the high school IA building.

TN: I learned in my research that you were an actor before you became a director. Why did you switch gears, and which position do you find more challenging?

JD: I was (and am, in some respects), a working actor for a number of years. I have always been interested in directing, however, right from my earliest days of fantasizing about what it would be like to make movies out of my favourite comic books and novels, to the mini-plays I would produce and direct in elementary school, to Fringe Theatre Festival projects later in life, and so on. I have spent time writing, producing, and directing stage shows since then, and have written a bit and produced a bit more for documentary films and narrative shorts. Feature film directing was a secret burning desire of mine, but it took a very long time for the right project to come along that would shake the fear out of me once and for all, and demand that I make the movie I wanted to make, with the folks I wanted to make it with, right here and right now; a project that would not take no for an answer. That project was The Doctor’s Case.

TN: You moved to New York for a while, was that while you were learning your craft as an actor?

JD: For the most part, yes: I started my career as a professional stage actor after leaving Vernon in the early-1990s. I took a year of English transfer courses at the local community college, but when it came time to go to university I decided theatre was my calling. I had spent a lot of time in community and high school musicals up until that point – performing, directing, building sets, what have you – and like so many star-struck kids before me, I wanted to see if I could make it to Broadway! So I took two years of theatre at the University of Victoria on Vancouver Island before transferring to the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York. It was a life-changing experience.

I learned a tremendous amount about the craft of acting in NYC, and even more about myself as a person. One of the most important things I learned there (although it took a few years to really take hold), was that I honestly didn’t want to be an actor in the traditional sense. The bright lights of the big city I had dreamt about for so long didn’t enthrall me as much as I thought they would, and the day to day grind of what it takes to be a consistently working actor in places like New York or Los Angeles woke me up to the realities of that lifestyle. I really love performing, but it is not the only thing I love to do, and I started to feel that in order to make any kind of sustainable career for myself as a jobbing actor, I would have to devote everything I had to the pursuit of that one thing. That realization kind of turned me off of the whole thing, to be perfectly frank.

Don’t get me wrong, I have the utmost respect for those friends and colleagues of mine who devote their lives to the craft, and as a director, I am particularly happy they choose to do so because it means I get to know and work with some of the best in the business, but I have always had difficulty sticking to one thing and one thing only. I need to do lots of different things to keep myself occupied.

After a year in New York I eventually made my way back to BC to complete an English Literature degree before accidentally falling in love with a little town in the central interior of British Columbia, called Wells. Wells is a crazy mixture of gold miners, forestry workers, artists, musicians, actors and writers nestled in the foothills of the Cariboo Mountains, with a history of mid-20th century hard rock gold mining that followed hard on the heels of a 19th-century placer gold rush centered around nearby Barkerville, BC. Barkerville is now a fully restored living history museum (the largest in Western North America, in fact), that employs professional actor-historians to deliver a variety of immersive and interactive educational programs in period costume throughout the original wooden town site, which consists of 140 restored buildings.

In the summer of 1998 I came up to Barkerville and Wells for what I assumed would be a unique but temporary summer acting gig. Twenty years later I am still here, although I have traded seasonal work as an historical interpreter for a full-time gig as the Director of Public Programming and Global Media Development. My wife, Danette (who I met at Barkerville, all those years ago), helps to produce and deliver award-winning educational programs here with me, and our twin daughters have just finished grade three at the Wells-Barkerville Elementary School (which boasts a total of 20 children, kindergarten to grade seven). From Wells I have managed to talk my way into some of the most amazing professional experiences of my life, including an internship at the National Theatre of the Czech Republic in Prague, with renowned avant-garde theatre director Charles Marowitz, and some short film projects, and a broadcast documentary that ultimately laid the groundwork for The Doctor’s Case. It’s an incredible situation to be in, and I feel very blessed to have found myself here.

TN: Out of all the Stephen King short stories, what attracted you most to this one? How did you first get involved with the Dollar Baby program?

JD: I remember listening to the three-part audiobook of Nightmares & Dreamscapes when it first came out in 2009, and was instantly flooded with memories of reading the collection back in 1991 during a transition year between high school and university. Back then I had two major literary loves: Stephen King and Sherlock Holmes. Imagine how excited I was to learn that King had written a Holmes story, in the style of Conan Doyle! The audiobook brought all that back to me, years later, with the added bonus of listening to Tim Curry, Pennywise himself! I read both The Doctor’s Case and Crouch End (my second favorite story in Nightmares & Dreamscapes). It also happened to be right at the time I was returning to Wells to work for Barkerville full-time, with six-month old twins in tow, and looking for something creative to do in my (very limited) spare time.

As I walked around Barkerville that summer I began imagining what it would be like to turn The Doctor’s Case into a film, using the variety of Victorian interiors at my disposal in this restored 19th-century gold rush town I had returned to after a couple of years away. At the time it was merely a creative exercise: after all, I did not have the authors permission to attempt an adaptation, and even if I did I could only shoot the interiors of any resulting project at Barkerville, since the exterior locations in a wooden mining town nestled in a mountainous valley covered by distinctly Canadian trees would hardly convince the viewer that he, she or they were in London, England (where the entirety of Kings story takes place). I still toyed with the idea though. Good ideas rarely stay quiet. But over the next few years it was relegated to a what if that I would dust off over a few beers with friends from time to time.

Then, in April of 2016, I happened to run into an old friend in Vancouver and, requisite beers consumed, started yacking about my unrequited desire to adapt The Doctor’s Case into a short film, and explained (as I usually did), how it would always be an unfulfilled dream because of the reasons outlined above. At which point she (the old friend) said: Have you ever heard of a Dollar Baby?

I had not. Which now seems utterly strange to me. How on Earth did I not know about a program King has administered since 1977 that granted limited rights to emerging filmmakers who want to adapt his unlicensed short stories? I still have no idea how that one slipped by me, but it did. Until April 2016. By May I was hanging out with Michael Coleman at Northern FanCon (an entertainment expo produced by my friend and colleague Norm Coyne in Prince George, BC), and casually mentioned the Dollar Baby idea to him. I wanted to know if he would consider playing Watson if we were successful in a hypothetical bid. He was enthusiastic about the idea so I promptly did nothing about it for nearly six months.

The following November I was shooting some promotional video in Barkerville with one of our immensely talented historical interpreters, JP Winslow. As I was transferring the captured video to my office computer, I started to think I had found a very interesting choice for Sherlock Holmes. One we’d definitely never seen before, but one that would work in a shared Stephen King/Sherlock Holmes universe, based (if nothing else), on the combination of JP’s inherent skills as an actor, and his own passionate interest in the history and writings of Arthur Conan Doyle. I asked JP the next day if he’d consider it. He called me crazy but still said yes. That afternoon I applied for the Dollar Baby program, and prepared to wait the suggested 4 to 8 weeks for a response. Which instead came three days later, contract attached. The game was afoot!

TN: What changes did you make, if any to make this your own as opposed to King’s original text?

JD: There are two obvious deviations we made from Kings original story. The first and I imagine most noticeable is the framing device we created as a means of telling the story within the story of The Doctor’s Case. In Stephen King’s short, the tale of Lord Hull’s murder and its subsequent investigation by Holmes and Watson is written like the majority Conan Doyle’s Holmes stories were, in the first person narrative by Doctor Watson some time after the events he’s describing have occurred. In this case, Watson tells the reader he’s nearing his 90’s and figures now is an appropriate time to record the one and only mystery he can recall solving before his slightly fabulous friend, Mr. Sherlock Holmes. The story then jumps directly to the meat of the matter. I knew I wanted to keep the older Watson’s voice throughout the film, both as an instrument of exposition and as means of preserving as much of Mr. King’s actually writing as possible. I also knew I wanted something a little more dramatic than having the older Watson sitting at a desk with pen in hand, literally writing the story as we went along. So I thought it would be best to have him talking with someone. The Captain Norton character evolved out of that idea, and I had a lot of fun creating a backstory for her once I knew Denise Crosby was on board.

The second change we made also includes a female character not in the original story, sort of. Fans who are familiar with King’s version of The Doctor’s Case will remember that Lord Albert Hull, diabolical Englishman and well-deserving murder victim, has three sons: William, Jory, and Stephen. I knew I wanted there to be a stronger female presence in our film than there is in the story (where there are only two women, Lady Rebecca Hull and Mrs. Hudson, neither of whom say much), and found it surprisingly satisfying to change the youngest child, Stephen, into a daughter and still have the plot make sense from a historical perspective. In doing so, I also selfishly guaranteed that I would be able to invite my cousin, Joanna Douglas, to play this new Hull daughter, which was important to me because she is a successful Canadian actress in her own right (with a principal role on a popular TV show called Being Erica, as well as a supporting role in another Stephen King project: Hulus 11/22/63). I hadn’t seen Joanna since she was three months old, so was particularly thrilled when she agreed to be in the movie. Since Stephen King had probably named the Stephen Hull character after himself, I decided to call our female version Tabitha Hull, after Stephen’s wife and fellow novelist, Tabitha King.

TN: In THE DOCTOR’S CASE, you have a very impressive cast including actress Denise Crosby (Pet Sematary) and William B. Davis (‘The Smoking Man’ in The X Files). How did these actors first get involved with a Dollar Baby film, and what did they bring to the table that impressed you enough to cast them?

JD: Denise Crosby was the key. She agreed to participate (I think), as a personal favor to me, which is amazing. I had met her back in 2013 when we held a mini-fan expo at Barkerville called, Lost in Time. Denise and I kind of hit it off then, and stayed in touch a bit via email. When I found out we got the Dollar Baby license I immediately asked Denise if she’d consider playing a role in the film (her pedigree being what it is, coupled with the fact that she is an extremely pleasant person to be around). It took a flight down to LA to work out the details, but she said yes without even seeing a script (which was great because I didn’t have one written at the time).

As I mentioned before, I knew I wanted a couple of female characters beyond Lady Hull and Mrs. Hudson, and the idea of an older Doctor Watson talking with someone rather than sitting down and writing the story was already forming, so I was presented with the extraordinary opportunity of developing the Captain Norton character with Denise in mind (not something I was expecting to do on my first kick at the can).

A family friend works at William Davis’s agency in Vancouver, so once I had Denise confirmed I immediately sought Mr. Davis out, as I knew we needed someone of Denise’s caliber to play against her in the 1940 framing scenes I had written (with input from Andrew Hamilton, our Lord Hull, who acted as creative consultant on the film). I am also a huge fan of The X-Files, so I had to take the shot. Thankfully, Mr. Davis said yes almost right away, and was very generous with his time and expertise on set.

It was literally a dream come true. When I was a teenager, Star Trek: The Next Generation and The X-Files were my two favorite TV shows, Pet Sematary was one of my favorite movies, and Stephen King and Sherlock Holmes books filled my shelves. Suddenly, here they all were colliding together right in front of me!

Michael Coleman (ABCs Once Upon A Time), was an old friend from my days as a working actor in Vancouver, Joanna Douglas (Being Erica, 11/22/63), is my cousin, and Erin Fitzgerald (Monster High, Ever After High, Ask the Storybots), is a dear friend from my days at the University of Victoria. The rest of the cast was made up of people I have known over the course of my careers in theatre and historical interpretation, and all of them said yes to the project without the slightest hesitation. I didn’t have to hold a single audition for any of the roles in The Doctor’s Case. I simply asked my friends and colleagues to participate, and am incredibly thankful they all said yes (including my wife, the incomparable Danette Boucher, who plays Mrs. Hudson in the film).

I have to admit that I was excited by our cast for another, totally geeky reason (one that Im sure fellow King fans will appreciate). We had a remarkable number of veterans of other Stephen King adaptations on our set. Denise Crosby played Rachel Creed in Pet Sematary, William B. Davis was in David Cronenbergs The Dead Zone, and the 1990 television miniseries Stephen Kings IT, we had another IT alumnus in the first cut of the film, Gaelan Bleasdale (now a Canadian hip hop artist called Evil Ebenezer, Gaelan played one of the Bowers gang as a kid; sadly, his short scene in The Doctors Case was ultimately cut), and my cousin Joanna played Doris Dunning in 11/22/63. Not bad for a Dollar Baby.

TN: So many Stephen King fans want adaptations to be as close to the book or story as possible. How do you handle the pressure to keep the fans happy?

JD: To be honest, I didn’t feel a lot of pressure to keep those Stephen King fans happy because I am one of those Stephen King fans! Seriously. I wanted this to work as a film as much as any fan would, and I was determined to keep as much of King’s writing in the script as possible. I mean his actual writing. Not just the plot and characters and themes, but whole passages of text. I think some adaptations of King’s work struggle to connect with audiences because they ignore the very thing (intentionally or otherwise) that makes a Stephen King story transcend its genre: his choice of words. King’s plotting is masterful, to be sure. His characters are more sharply drawn than most. But the glue that holds everything together the thing that makes you want to keep turning the page no matter how late into the night you’ve been reading – is his narrative voice. Without that authentic voice to guide an audience through the turbulence of his imagination, it becomes easier to focus on the surface aspects of a Stephen King story: to trade important thematic details for jump scares, for example, or cut too quickly from one scene to another without allowing concepts to fully develop.

Preserving that voice can be very difficult when transitioning from page to screen, however. Movies are not books. Its normally better to show than to tell on film. It is unrealistic to think that the majority of filmmakers will have a chance to work with a story that requires near-perfect transcription of not only dialogue but entire descriptive passages to ensure the whole thing makes sense, and to ensure the Stephen King-ness of a story set in another authors world is upheld.

Fortunately, The Doctor’s Case is exactly that kind of story. It’s very nature allows for a massive amount of tell on screen. It’s a Sherlock Holmes story. It’s meant to be wordy. Our collective fantasy version of the Victorian era in England and abroad, thanks in large part to Hollywood versions of Charles Dickens and Arthur Conan Doyle we’ve all grown up with, involves a lot of standing around and talking. Therefore, it doesn’t seem out of place to have these characters do precisely that.

As Sherlock points out, Inspector Lestrade relays a remarkably large body of information in a remarkably short period of time while standing in 221b Baker Street, and not only does it play as natural to have him do so in a 19th-century setting, it is absolutely vital to the presentation of the murder mystery plot that he does. I wouldn’t necessarily approach every King story that way, but for my first adaptation I was buoyed by the fact that my inner fan was going to be very pleased with our choice to be slavishly faithful to the original text of The Doctor’s Case.

To be honest, I feel more pressure to appease the Sherlock Holmes fans out there. By necessity we’ve taken slightly non-canonical approaches to a couple of the finer details of our shared King-Conan Doyle universe. While I firmly believe these choices are justified given a) our budget, and b) the fact that this is our version of King’s version of Conan Doyle’s character (at least, that’s what I keep telling myself), but I’m always a little nervous about how Sherlockians will react to certain choices.

Those folks can be ruthless (just kidding).

All joking aside, I do feel a responsibility to our audience – many of whom will be lovers of Stephen King, Sherlock Holmes, and/or movies in general – and while I suppose I can’t expect everyone to agree with every choice we’ve made, I believe there is enough in The Doctor’s Case to surprise and delight casual observers and diehard fans alike.

TN: There were a lot of things I was impressed with in your film: the music and the sets, both were amazing. Tell us about both of them.

JD: Serendipity has been our friend and mantra throughout all of our work on The Doctor’s Case. So many of the incredible opportunities we’ve been able to take advantage of have literally walked into the room at exactly the right time, as if to keep daring us to dream bigger and work harder. The music and the locations both started as one thing, then quickly became something much bigger than we would have dared dream of at the very beginning of this process.

As soon as we realized The Doctor’s Case was a go, my producing partner Norm Coyne and I started talking with a musician friend of ours, Jeremy Breaks, about helping with the score. Norm and Jeremy have been tight for years, and when not touring as lead guitar for the Dallas Smith Band, Jeremy (or Jer, as we call him), has recently started writing music for short film and video projects. As we were sifting through Jeremys schedule and trying to decide whether he would tackle the entire score for The Doctor’s Case himself or bring in some collaborators, I happened to be presenting a reading of Charles Dickens A Christmas Carol during Barkervilles Old Fashioned Victorian Christmas event. After the reading, a couple who had originally been sitting at the back of the auditorium but who had slid further and further toward the front seats as the reading progressed, came up to me afterwards to introduce themselves and let me know how much they had enjoyed the presentation. Ken Marshall and his partner, Maria Lui. They told me their names and my jaw nearly hit the floor.

It just so happens that, as a teenager, I went through a short but glorious industrial music phase while trying and failing to break into the local skateboarding scene. I listened to a lot of hard-core music back in the day, and for a couple of years my absolute favorite was the music of a pioneer industrial band called Skinny Puppy – and Skinny Puppy’s music was produced by a guy named Ken hiwatt Marshall. This guy. Standing in front of me. A guy with a platinum record hanging on his studio wall (thanks to a collaboration with Linkn Park), was standing there telling me how much he’d enjoyed my show. I couldn’t believe it.

Before we said goodbye, I found myself telling Ken and Maria that there was another project I was working on that I would love a chance to tell them about sometime. They told me to tell them about it right then and there. So I told them about The Doctor’s Case and what we wanted to do with it. They said they wanted to help with the music. Right then and there.

From that point forth our trio of composers, Ken, Maria, and Jer, worked in tandem on the soundtrack, with Jer writing guitar and banjo riffs, while Ken experimented with a room-sized analogue synthesizer he had access to in LA in between tour dates with his new industrial band, Black Line (who in turn opened for Depeche Mode all across Europe last summer), and Maria began scoring our overture. To top it off, the three were completely open to incorporating the melody of a song my aunt had written for me back when I was a baby, which became the tune Sherlock Holmes plays on his violin at the very end of the film. Another dream had, serendipitously, come true.

It was kind of like that with our locations, too. Or, at least, the National Historic Site equivalent of meeting the producer of one of your favourite bands and having him volunteer to supervise your music team. A couple of weeks before I met Ken and Maria in Barkerville, I was in Jasper, Alberta at an annual tourism industry conference. While there, I ran into an old friend from Victoria, Kate Humble. Like me, Kate had transitioned from a traditional theatre career into a career in historical interpretation, and at that time was the visitor services coordinator at Craigdarroch Castle National Historic Site, a spectacular Victorian mansion and former home to the wealthy industrialist Dunsmuir family, designed and built in the 1880s to resemble a four-storey Scottish castle.

As I mentioned earlier, my original idea was to shoot the interiors of our film in Barkerville, and find some other places to film the exteriors. If we were able to use Craigdarroch Castle as Hull House (I found myself saying out loud to Kate), then we’d be able to shoot interiors and exteriors in the same place. To my utter astonishment, she said she would talk with her team about it. Now, I wasn’t ever expecting to film The Doctor’s Case at a place like Craigdarroch. Major studio movies like Little Women shoot there, and their location day rate is (deservedly) very high. We would never be able to afford it, even if they did say yes. And yes, they did say yes. They even did one better. As long as we promised to shoot between 5:30 pm and 2:30 a.m. each day (which we regularly pushed to 5:30 am and the good folks at Craigdarroch were kind or crazy enough to allow it), then our location fee would be drastically reduced, in light of our meagre budget, and their desire to showcase the castle in our film.

Once we knew we were bound for Victoria to shoot at the castle, it seemed only logical we should try to shoot as much of the rest of the film there as we could. Another colleague from BC’s heritage tourism industry is Jan Ross, who operates Emily Carr House National Historic Site, the birthplace of renowned Canadian painter and writer, Emily Carr. Jan was extremely helpful, and let us use the dining room of Emily Carr House as our Baker Street apartment, as well as an impressive set of interior stairs that allowed us to create the illusion that the apartment was on the second floor of a building, which Holmes and Watson’s residence famously is, but Emily Carr Houses dining room is not. We then managed to get a permit from the city of Victoria to shoot the exterior of Baker Street in Bastion Square, which is full of 19th-century stone buildings.

We saved one interior scene to film in Barkerville, which we did several weeks after the Victoria shoot. It’s a flashback scene depicting the birth of Jory Hull, Lord Albert Hull’s middle child. For that we used an authentic 1860’s country doctors office in Barkerville, which also happens to be a National Historic Site of Canada. So, in the end, we were able to showcase three separate National Historic Sites in British Columbia in one 65-minute Stephen King film. Sites that are all spectacular places to visit, by the way (shameless tourism plug).

TN: What was the main goal you wanted to achieve with this film?

JD: My main goal was to finally make the film I had been dreaming about making, and make it with a group of people I was thrilled to team up with every day. Of course I want people to like it, heck, I just want people to be able to see it, but honestly the fact that I was simply able to make this movie to the best of my ability, at this particular time with these exceptional people means my real goal has already been met. Having Stephen King watch it and (hopefully), like it is an associated goal, and I’m working on that, but even if that never happens I must say I have been completely satisfied by this experience so far.

TN: Where was the movie filmed specifically, and were there any obstacles to overcome while filming on location?

JD: Specifically, the movie was filmed on location at Craigdarroch Castle, Emily Carr House, Heritage Acres and Bastion Square in Victoria, British Columbia, and at Barkerville Historic Town & Park in Barkerville, BC. There were many obstacles to overcome in all of our locations. As I mentioned before, we were shooting at Cragdarroch Castle all night long. This meant shooting our Baker Street scenes at Emily Carr House and Bastion Square, as well as the interior carriage scenes at Heritage Acres, during the day – then shooting the Hull House scenes at Craigdarroch at night. We had a very small crew, so this meant everyone was pulling double and triple shifts, fueled by great catering (thanks to Sara Mushansky), lots and lots of coffee, and sheer force of will. It was a challenging shoot for that reason alone. Throw in the fact that the majority of the interior Hull House scenes we filmed at night took place during the day, and suddenly we have serious lighting challenges to deal with.

We were also shooting in Victoria in April, which meant expensive accommodations for our cast and crew, and no rain. You’d think no rain would be a good thing, but in our case it was a real challenge. Anyone who has read Stephen King’s The Doctor’s Case will tell you that rain is practically its own character in the story. So much depends on, or is affected by, the rain. And in Victoria in April there is no rain, only bright, beautiful sunshine, and acres of spring flowers (another shameless tourism plug). We wound up having to be very creative with how we invented rain for our version of The Doctor’s Case, and although it was both a practical and digital challenge to do so on a micro budget, we managed to pull it off.

When we got to Barkerville in June things ran pretty smoothly. Although we were only there for a day shooting one short scene there was still the challenge of filming the one flashback in the movie that takes place significantly prior to most of the main action. This meant we had to de-age Lord Hull a bit, and find another actor to play a younger version of Lady Hull. Serendipity was our friend once again, however, and while we were preparing to shoot I ran into a young woman I knew who was traveling to Wells to visit family, would be here when we needed her, had some acting experience, and looked remarkably like a younger version of Michelle Leiffertz, our Lady Hull (and production designer, by the way). We needed to use an actor other than Michelle not because we didn’t want to keep her for the scene, but because by June of 2017 she’d returned to Italy, where shed been travelling with her family on a year abroad adventure when I hauled her back to Canada for two weeks to design and act in The Doctor’s Case. We also didn’t have a real baby to use as the newborn Jory Hull. We had to be creative there, too, and rely on some dramatic conventions that fit the purposefully theatrical nature of the majority of our Hull family flashbacks.

TN: How long was the film shoot and the process from start to finish?

JD: We shot for twelve days (and looooong nights) in Victoria, and one day in Barkerville for a total of thirteen production days. We then spent nearly seven months in post-production. We managed to get it all finished within the year allotted by the Dollar Baby contract, however, and that was a pretty astonishing feat in retrospect.

TN: You did something in this Dollar Baby I have never seen before: you added a scene after the credits. Was this on purpose as a teaser for a possible sequel, or just a treat for King fans once the credits were over?

JD: I put in the post-credit scene for a couple of reasons. The first reason was I wanted to give some resolution to the Captain Norton/Older Watson story wed invented for our framing device, without having it interfere with the main plot of the film. It does tease a possible sequel, or provide the jumping off from a pilot episode of some sort to the remainder of a hypothetical series, but that was more for fun than out of any expectation of actually being able to continue the story (as much as I would love to). It also seemed to fit with the 1940’s setting of the Norton/Watson scenes, and harken back to a time for moviegoers when cliff hanger endings were a regular part of the serialized short films that would often play before feature presentations at movie theatres a generation or more ago; the same kind of movie theatres a young Stevie King might have found himself frequenting back in Maine in the 1950’s. So, yes: a treat for the fans, and for one fan in particular.

TN: What is the greatest moment so far with the success of THE DOCTOR’S CASE?

JD: There are too many to count. I think, to be totally honest, it was the day I placed a Blu-ray disc containing the final version of The Doctor’s Case in the mail, addressed to Stephen King. I have no idea if he’s watched it yet (I suspect he hasn’t had the chance), but that accomplishment alone actually finishing the film and sending it to Stephen King was worth all of the work and stress and education and raw determination that had gone into making The Doctor’s Case. If I had to choose one moment, that might just be it. But there really have been so many.

TN: What Stephen King story would you like to adapt on a much lager scale?

JD: There are so many of those, too! I would probably be happy for the rest of my life making nothing but Stephen King movies. Really, I would. If I had to pick just one, though, and the budget was sufficient to do it properly, then I would have to say my dream project would be an adaptation of King’s 1987 novel, The Eyes of the Dragon.

TN: As a Stephen King fan, what are your thoughts on the film adaptations that are coming out recently, and his new novels compared to his older works?

JD: I love it all. I really do. Some of the new adaptations have been great (the new IT, 11/22/63, and 1922 come to mind), some have been so-so (Gerald’s Game), and some have missed the mark completely (I still haven’t been able to get past the first act of The Dark Tower, I am ashamed to admit; but I will keep trying). Regardless, I still love them all. It’s the same with his newer novels and stories. I am still having a blast reading them. I think Dr. Sleep and The Outsider contain some of his finest work. And when it comes right down to it, they are Stephen King. Bad Stephen King is better than no Stephen King, and except for a few of the films there really isn’t that much bad Stephen King. Even The Tommyknockers is better than most of the genre novels I was reading at the time of its release, and King barely remembers writing that one!

TN: Where can fans see your film, and will it be playing at film fests around the world?

JD: Anyone who wants to see the film can come to Barkerville and I will personally show it for free. I’m actually allowed to do that, so start making your vacation plans, everybody (final shameless tourism plug)! As for other opportunities: according to our Dollar Baby contract with King, we cannot distribute the film commercially, so the only place other than Barkerville it can be seen is at established film festivals and under certain not-for-profit conditions. We’ve applied for more than 30 international festivals over the past six months, and have been fortunate enough to be officially selected by a number of them already. We’re still waiting to hear back from more than a dozen that take place this fall, but so far we’ve screened at the Julien Dubuque International Film Festival (our world premiere), the Adrian International Film Festival, Cinema CNC Festival, Cariboo Chilcotin Film Festival, Mid-Tennessee Film Festival (where we won awards for Best Feature and Best Actor), Comicpalooza Film Festival (where we won for Best Cinematography, Best Costumes, and Best Actress), the Penti-con Festival, and the New Hope Film Festival (where we won for Best Period Film). Next week we head to the Kew Gardens Festival of Cinema (and are nominated for Best Cinematography and Best Editing there), and the week after that we’re at three more: the Regina International Film Festival, World Con 76 Film Festival, and the Diamond in the Rough Film Festival.

TN: What is the best advice you can give to future filmmakers and those who wish to make a Dollar Baby film someday?

JD: Don’t panic. Learn from everyone. Don’t be afraid to admit when you don’t know something, and don’t feel ashamed to ask advice from someone who does. If you’re offered a chance to work on a Dollar Baby film and you love Stephen King, do it.

TN: Final question: What is next for James Douglas?

JD: Over and above my day job at Barkerville and ensuring I spend quality time with my wife and kids, there are a few projects on the horizon. Andrew Hamilton (Lord Albert Hull), Stu Cawood (William Hull). and I are writing a vampire western we hope to shoot in Barkerville this winter. I am also directing a short film written and starring JP Winslow (Sherlock Holmes) in September, and I am currently writing historical scripts for a television documentary that my co-director on The Doctor’s Case, Len Pearl, is producing and directing for broadcast in 2019. Other than that, I could use a little more sleep!

I’d like to thank James Douglas for his wonderful film, and his wonderful enthusiasm with this interview. I truly cannot remember when I have interviewed someone with such passion for his craft. This truly made this exciting for me as well. I hope all of you will enjoy this article, and remember, if you get the opportunity to find an Independent Film Festival near you, look to see if …THE DOCTOR’S CASE…a film directed by James Douglas is among the agenda.

Tags: James Douglas, james douglas interview

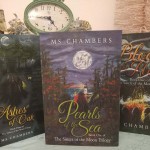

THE SISTERS OF THE MOON Trilogy – Samantha Chambers

THE SISTERS OF THE MOON Trilogy – Samantha Chambers (Italiano) UNA SPIEGAZIONE PER TUTTO – Gábor Reisz

(Italiano) UNA SPIEGAZIONE PER TUTTO – Gábor Reisz (Italiano) CIVIL WAR – Alex Garland

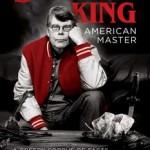

(Italiano) CIVIL WAR – Alex Garland STEPHEN KING NOT JUST HORROR – Hans-Ake Lilja

STEPHEN KING NOT JUST HORROR – Hans-Ake Lilja SACKHEAD:The Definitive Retrospective on FRIDAY THE 13th PART 2 – Ron Henning

SACKHEAD:The Definitive Retrospective on FRIDAY THE 13th PART 2 – Ron Henning NEON NIGHTMARES: L.A. Thrillers Of The 1980′s – Brad Sykes

NEON NIGHTMARES: L.A. Thrillers Of The 1980′s – Brad Sykes THE AFTERLIFE BOOK: Heaven, Hell, And Life After Death – Marie D. Jones & Larry Flaxman

THE AFTERLIFE BOOK: Heaven, Hell, And Life After Death – Marie D. Jones & Larry Flaxman POPULATION PURGE – Brian Johnson

POPULATION PURGE – Brian Johnson LETTERS FROM A DEAD WORLD – David Tocher (review & interview)

LETTERS FROM A DEAD WORLD – David Tocher (review & interview)